Water Properties

Before we begin looking at the properties of water, maybe you'd like to find out how much you know about water by taking a little True/False quiz concerning water properties. You might be surprised at what you find.

What are the physical and chemical properties of water that make it so unique and necessary for living things? When you look at water, taste and smell it - well, what could be more boring? Pure water is virtually colorless and has no taste or smell. But the hidden qualities of water make it a most interesting subject.

Water's Chemical Properties

You probably know water's chemical description is H2O, that is one atom of oxygen bound to two atoms of hydrogen. The hydrogen atoms are "attached" to one side of the oxygen atom, resulting in a water molecule having a positive charge on the side where the hydrogen atoms are and a negative charge on the other side, where the oxygen atom is. Since opposite electrical charges attract, water molecules tend to attract each other, making water kind of "sticky." The side with the hydrogen atoms (positive charge) attracts the oxygen side (negative charge) of a different water molecule. (If the water molecule here looks familiar, remember that everyone's favorite mouse is mostly water, too).

All these water molecules attracting each other mean they tend to clump together. This is why water drops are, in fact, drops! If it wasn't for some of Earth's forces, such as gravity, a drop of water would be ball shaped -- a perfect sphere. Even if it doesn't form a perfect sphere on Earth, we should be happy water is sticky. Water is called the "universal solvent" because it dissolves more substances than any other liquid. This means that wherever water goes, either through the ground or through our bodies, it takes along valuable chemicals, minerals, and nutrients.

Pure water has a neutral pH of 7, which is neither acidic nor basic.

Water's Physical Properties

- Water is unique in that it is the only natural substance that is found in all three states -- liquid, solid (ice), and gas (steam) -- at the temperatures normally found on Earth. Earth's water is constantly interacting, changing, and in movement.

- Water freezes at 32° Fahrenheit (F) and boils at 212° F (at sea level, but 186.4° at 14,000 feet). In fact, water's freezing and boiling points are the baseline with which temperature is measured: 0° on the Celsius scale is water's freezing point, and 100° is water's boiling point. Water is unusual in that the solid form, ice, is less dense than the liquid form, which is why ice floats.

- Water has a high specific heat index. This means that water can absorb a lot of heat before it begins to get hot. This is why water is valuable to industries and in your car's radiator as a coolant. The high specific heat index of water also helps regulate the rate at which air changes temperature, which is why the temperature change between seasons is gradual rather than sudden, especially near the oceans. Water has a very high surface tension. In other words, water is sticky and elastic, and tends to clump together in drops rather than spread out in a thin film. Surface tension is responsible for capillary action, which allows water (and its dissolved substances) to move through the roots of plants and through the tiny blood vessels in our bodies.

Here's a quick rundown of some of water's properties:

- Weight: 62.416 pounds per cubic foot at 32°F

- Weight: 61.998 pounds per cubic foot at 100°F

- Weight: 8.33 pounds/gallon, 0.036 pounds/cubic inch

- Density: 1 gram per cubic centimeter (cc) at 39.2°F, 0.95865 gram per cc at 212°F

Here are some water volume comparisons:

- 1 gallon = 4 quarts = 8 pints = 128 fluid ounces = 231 cubic inches

- 1 liter = 0.2642 gallons = 1.0568 quart = 61.02 cubic inches

- 1 million gallons = 3.069 acre-feet = 133,685.64 cubic feet

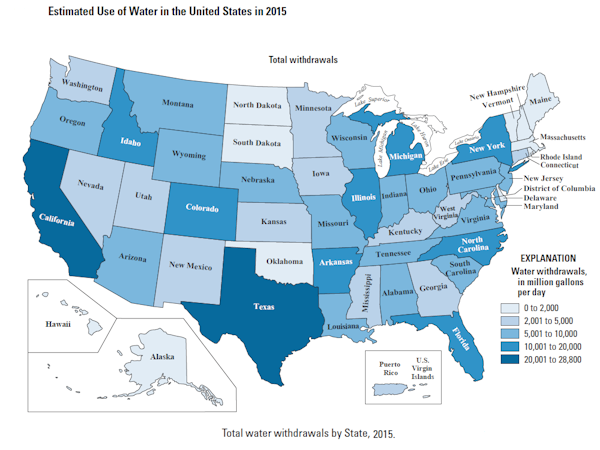

Total Water Use In The U.S. In 2015

The water in the Nation's rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and underground aquifers are vitally important to our everyday life. These water bodies supply the water to serve the needs of every human and for the world's ecological systems, too. Here in the United States, every 5 years the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) compiles county, state, and National water withdrawal and use data for a number of water-use categories.

Water use in the United States in 2015 was estimated to be about 322 billion gallons per day (Bgal/d), which was 9 percent less than in 2010. The 2015 estimates put total withdrawals at the lowest level since before 1970, following the same overall trend of decreasing total withdrawals observed from 2005 to 2010. Freshwater withdrawals were 281 Bgal/d, or 87 percent of total withdrawals, and saline-water withdrawals were 41.0 Bgal/d, or 13 percent of total withdrawals. Fresh surface-water withdrawals (198 Bgal/d) were 14 percent less than in 2010, and fresh groundwater withdrawals (82.3 Bgal/day) were about 8 percent greater than in 2010. Saline surface-water withdrawals were 38.6 Bgal/d, or 14 percent less than in 2010. Total saline groundwater withdrawals in 2015 were 2.34 Bgal/d, mostly for mining use.

Okay. You think you now know water? Take The Quiz. No Cheating.